Software Testing

Software systems are only useful if they do what they are supposed to do. This is increasingly important given the vital safety-critical roles modern software systems play. Unfortunately, proving that a system is correct is exceedingly difficult and expensive for large software systems. This leads to the fundamental tradeoff at the heart of most commonly applied testing approaches:

Given a finite amount of time and resources, how can we validate that the system has an acceptable risk of costly or dangerous defects. [Bob Binder]

Given the constraints above, the most prevalent quality validation approach in use today is automated testing (followed by code reviews). Unfortunately, as Dijkstra noted in 1969:

Program testing can be used to show the presence of bugs, but never to show their absence! [Edsger Dijkstra]

This is because what we are evaluating is whether the probability that there are no bugs in a system given that the tests pass is not actually 0. Since tests themselves are programs (and can have bugs) and specifications are often incomplete or imprecise we therefore must admit that the chance of a defect slipping through a set of tests is > 0 (online discussion).

Testing Process

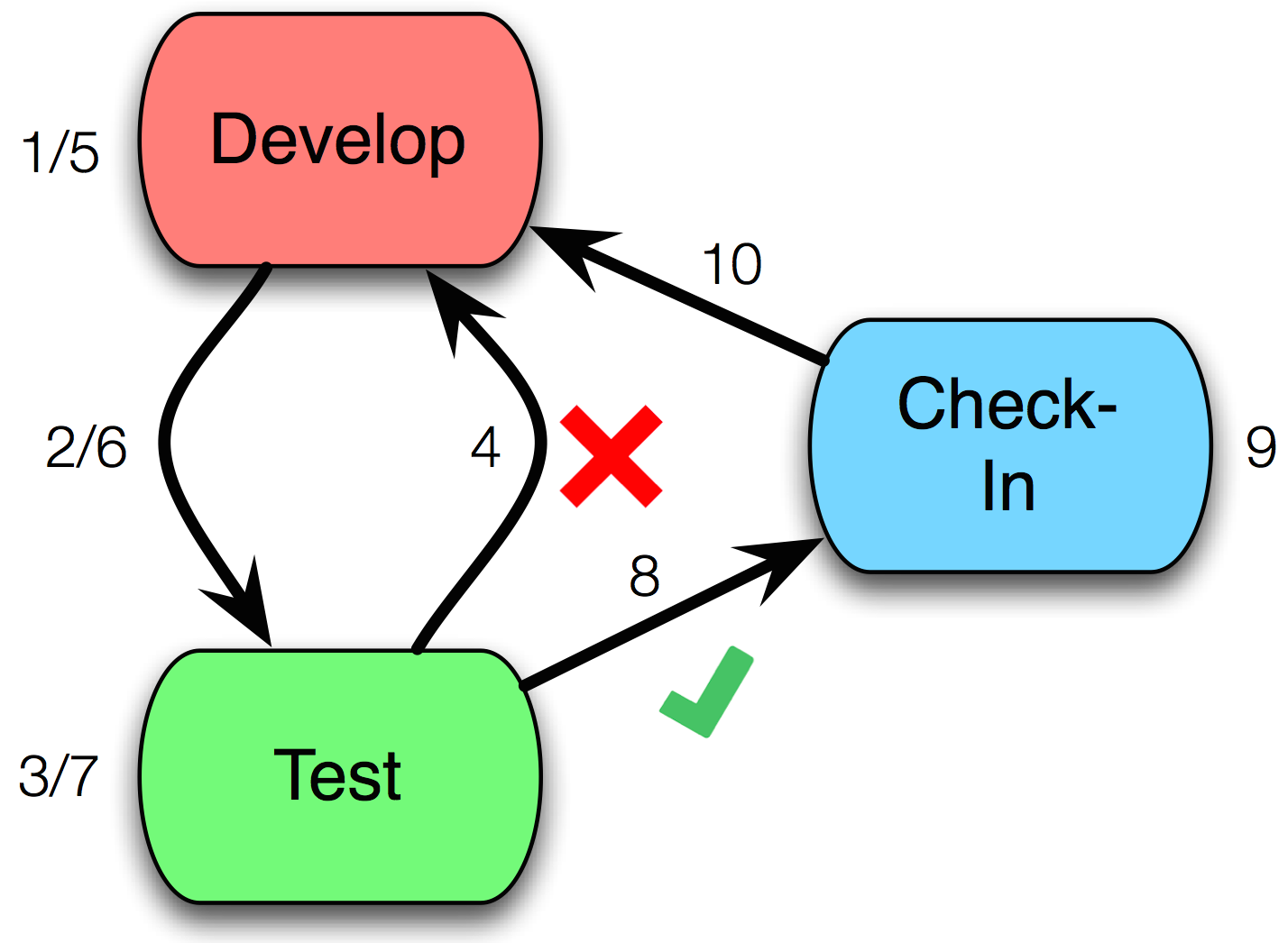

The modern test cycle is summarized below. The cycle between steps 1-7 can occur many times before the code is ready to commit.

- Develop some new code.

- Deploy to testing environment.

- Run your tests.

- Test fails.

- Try to fix the failure through more development.

- Deploy to testing environment.

- Run the tests again.

- Test passes.

- Commit/push change.

- Pull new changes.

Steps 2/7 may not happen on small teams or when testing happens solely on a single development machine. The code that is developed in steps 1/5 could involve either writing test or product code. In Test-Driven Development (TDD) the first develop step would be to write tests for features that haven’t been written yet to guide future development.

Terminology

A number of different terms are commonly used in the testing space:

SUT/CUT: System / code under test. This is the thing that you are actually trying to validate.Glass box testing: When testing in a glass box manner one typically carefully examines the program source code in order to identify potentially problematic sets of inputs or control flow paths. More details can be found in the Glass box testing reading.Black box testing: Black box testing validates programs without any knowledge of how the system is implemented. This form of testing relies heavily on predicting problematic inputs by examining public API signatures and any available documentation for the CUT. More details can be found in the Black box testing reading.Effectiveness: The simplest way to reason about the effectiveness of a test or test suite is to measure the probability the test will find a real fault (per unit of effort, which can be something like developer creation / maintenance time or number of test executions).Testability: Some systems are significantly easier to test than others due to the way they are constructed. A highly testable system will enable more effective tests for the same cost than a system whose tests are largely ineffective (or require an outsized amount of creation and maintenance effort). More details can be found in the Testability reading.Repeatability: The likelihood that running the same test twice under the same conditions will yield the same result.

Properties of tests

Kinds of tests

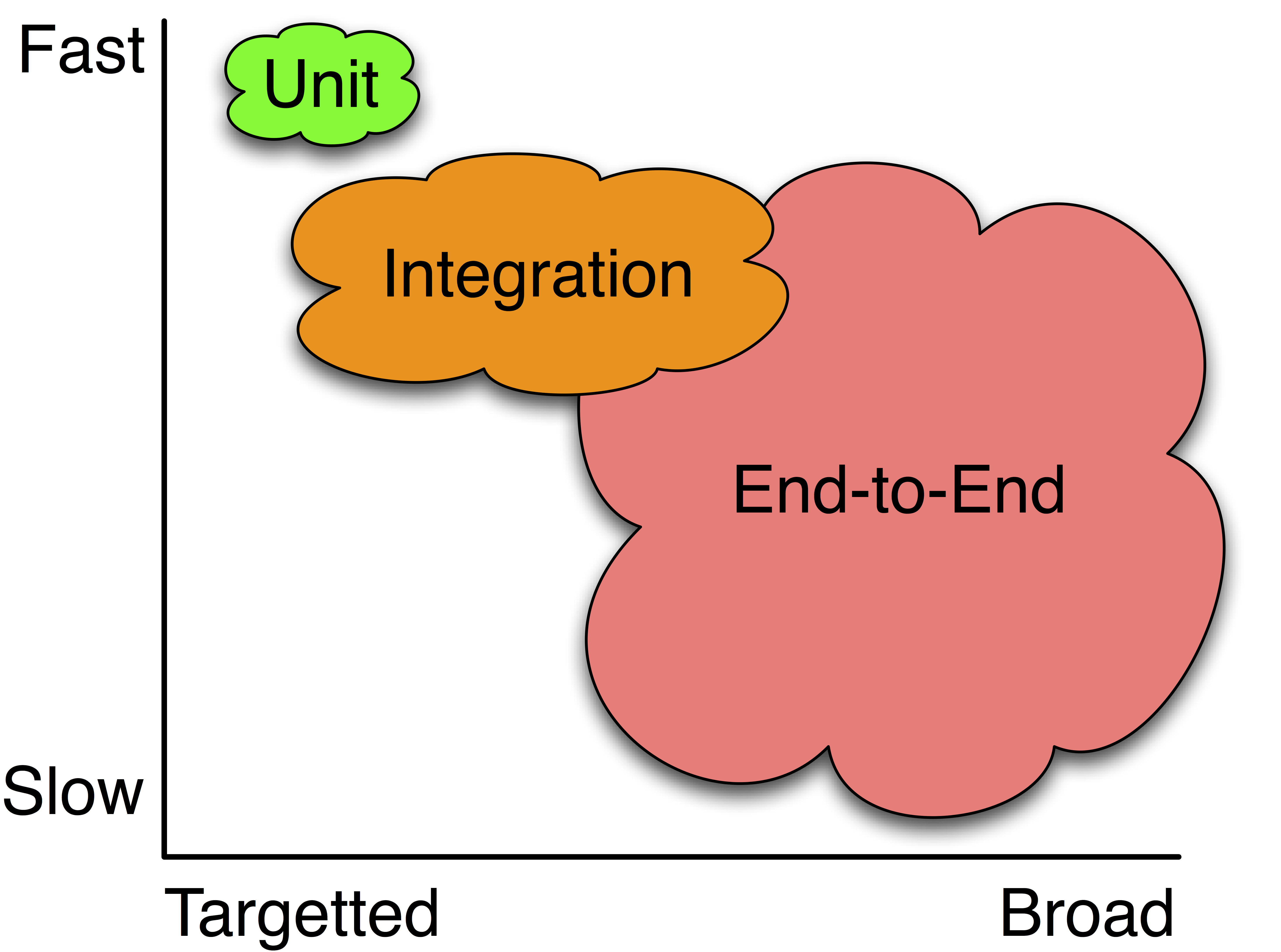

There are a number of different levels of test; these range in size, complexity, execution duration, repeatability, along with how easy they are to write, maintain, and debug.

Unit: Unit tests exercise individual components, usually methods or functions, in isolation. This kind of testing is usually quick to write and the tests incur low maintenance effort since they touch such small parts of the system. They typically ensure that the unit fulfills its contract making test failures more straightforward to understand.Integration: Integration tests exercise groups of components to ensure that their contained units interact correctly together. Integration tests touch much larger pieces of the system and are more prone to spurious failure. Since these tests validate many different units in concert, identifying the root-cause of a specific failure can be difficult.End-to-End: Also referred to as acceptance testing, these tests typically validate entire customer flows. They are especially useful for validating quality attributes (such as performance and usability) that cannot be captured in isolation. These tests are great for ensuring that the system behaves correctly but provide little guidance for understanding why a failure arose or how it could be fixed.A|B: A special subset of testing that is typically employed in production environments. In A|B testing, two different versions are compared at runtime to validate which one performs ‘best’. A|B testing is often used to validate business decisions, rather than evaluate functional correctness.Smoke/Canary: This is a subset of a test suite that typically executes quickly, is highly reliable, and has high effectiveness. Smoke tests try to expose a fault as quickly as possible, making it possible to defer running large swaths of unnecessary tests for a system that is known to be broken (for example, if you have an error in your data model that touches your whole system, there is no need to run slow integration and end-to-end tests).

For additional reference, take a look at this in-depth talk about how Google tests their systems.

Why not test?

There are a number of reasons why software systems are not tested with automated suites. These range from “bad design” to “slow”, “boring”, “doesn’t catch bugs” and “that’s QA’s job”. Ultimately, testing does have a cost: tests are programs too and take time to write, debug, and execute and must also be evolved along with the system.

One core paradox of automated test suites is how they are used. If you think that a test only provides value when it fails by catching a bug that would have otherwise made it to production, then that all passing tests are just a waste of computational cycles. At the same time though, passing tests do give us the warm feeling that we have not introduced unexpected regression bugs into our systems. But at the same time, these feelings only work if we believe our test suite is capable of finding faults and could fail. Yes: this contradicts the ‘we should only run failing tests’ implication above.

An area of interesting future research would be to figure out how often a suite needs to fail to impart trust, while also figuring out how few passing tests you could run to have a sense of confidence in your automated suite.

Common testing assumptions

It has been long held that the cost of fixing a fault rises exponentially with how late in the development process (e.g., requirements, design, implementation, deployment) the fault is detected. This statement arises from several influential studies Barry Bohem performed in the 60s and 70s. A more in-depth description of these costs can be found here or here.

There is a more modern discussion however that openly wonders if these costs are not relevant for more modern-styles of software development and programming languages.

It is also important to accurately consider the costs of automated test suites. Writing tests takes time. Executing tests takes time. Diagnosing failing tests take time. Fixing tests that were incorrect takes time (tests are programs too!). But catching real faults can save money, as can increase velocity enabled through better understanding how shippable your code is. While it is easier to account for the costs than the benefits, most large teams have invested heavily in automated test suites, although many large teams are actively investigating test prioritization and minimization schemes to reduce the delay between making a change and having a meaningful test result.

References

Another great talk about how Google stores its source code.

Steve Easterbrook testing 1.

Steve Easterbrook testing 2.

Laurie Williams black box testing notes.

Laurie Williams white box testing notes.

Laurie Williams automated testing notes

MIT testing slides.

Jim Cordy’s quality assurance course.