Specifications

A ‘wicked problem’ is one that can only be clearly defined and understood by solving it. Peters and Tripp observe that,

‘This paradox implies that one must solve a problem once to define it and then solve it again to create a solution that works.’

Software development is often considered a wicked problem because high-level software requirements can have important ramifications for the low-level implementation of the system (and vice versa). That is, without starting making implementation decisions one cannot fully understand the implications on the requirements themselves.

Wicked problems often similar characteristics:

- No definitive formulation. Given the diverse set of stakeholders involved in real software systems, each have their own set of priorities and constraints that will often be in contention with one another.

- No stopping rule. This is always true for software: systems are never fully ‘done’, bugs always exist, and new features are always possible.

- Solutions are not true-or-false, just good-or-bad. For most problems, no one software design is absolutely the best. Every software design has a set of benefits and tradeoffs.

- Solutions to wicked problems often only have one chance for success. Software systems are so expensive to produce that it is impractical to expect a team to generate multiple different complete solutions to see what works best.

Fortunately, there is a path forward (if not a solution) for wicked problems and that is through interaction and discussion amongst stakeholders as observed by Mary Poppendieck,

‘The appropriate way to tackle wicked problems is to discuss them. Consensus emerges through the process of laying out alternative understandings, competing interests, priorities, and constraints.’

Specifications are documents used to describe a software system. Specs connect customers and engineers and help to ensure that different parts of the implementation work together. A spec will define both what the system does and how the behaviour can be tested for correctness. Different specs are useful for different stakeholders (e.g., designers, developers, testers, managers, ops, customers…).

At their core, all software specifications are abstractions that abstract away some kinds of details so stakeholders can focus on other details (e.g., Developers and Operations teams might collaborate on defining a deployment specification that specifically maps software elements to data centres).

Requirements

There are two broad categories of requirements:

- Functional requirements: These describe what the system must do. For example, “The system shall let the user logout with a single click” provides a specific feature the system must have.

- Non-functional requirements: These describe properties the system must have (often called quality attributes). For example, “The system should be usable” describes a property the system should exhibit.

It is important to remember that requirements describe what a system is to do, but not how it is to be done. For example, a spec might specify that “a list should be sortable in 0(nlogn) time” but not that “a list will be sorted using quicksort”.

Non-functional properties play important roles in most systems. These include the ‘ilities’ like reliability, security, usability, complexity, evolvability, performance, etc. Like functional properties, these also often conflict with one another. For example, designing a system that has low complexity, high performance, and good usability is extremely challenging, while designing a system that has only two of those properties is significantly easier. By engaging stakeholders in discussions about requirements we can help them to understand which are most important for the successful operation of the system.

That software failures are costly has been well described in practice. One of the most common reasons behind these failures can be summarized as “specification failures”. Because of this, correctly capturing and understanding requirements is fundamental for projects being successful; this is also why Agile methodologies incorporate customers onto development teams to try to decrease requirements misunderstandings.

While there are many properties stakeholders should keep in mind when recording software specifications, these four are especially important.

- Complete: A spec that does not completely describe the requirements provides opportunities for misunderstanding between stakeholders.

- Consistent: Conflicting requirements also generate misunderstandings that can make knowing the right behaviour impossible to understand.

- Precise: Natural language is inherently imprecise while source code must be precise for the computer to be able to interpret it. This disconnect, and the fact that specs cannot be automatically validated, means imprecise language can further complicate understanding intended behaviour.

- Concise: While the above points seem to say that “more is better” when it comes to specifications, having “more” also provides more space for imprecision and inconsistency to become problems.

During the requirements elicitation process several different types of requirements can be gathered in addition to the functional and non-functional properties described above; these include:

- Design constraints: Organizations typically have design constraints that must be imposed on software systems; these can include regulatory compliance, budget, languages and frameworks, and development/security process requirements.

- Environmental constraints: Software systems do not exist in isolation; environmental constraints ensure that the new system will work with existing systems. These constraints often the mandate execution environment (e.g., the operating system, library limitations, services that can be consumed and must be provided) and operational expectations (e.g., expected input, performance constraints, disaster recovery).

- Preferences: Not all requirements are equal, preferences provide a mechanism to explicitly rank requirements should they come in conflict.

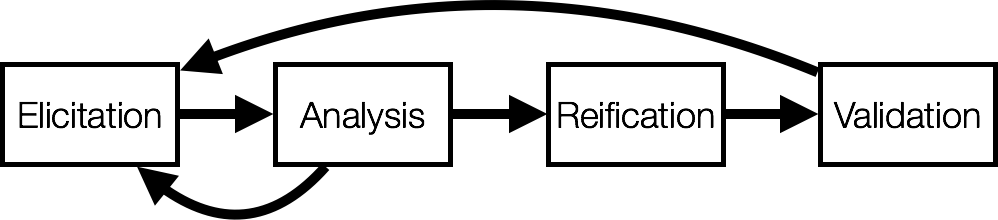

During this process requirements are first elicited (gathered) from various project stakeholders. Next these requirements are modelled to gain a more concrete understanding of what is actually needed. If any further clarifications are needed here it is often quickest to go back to the stakeholder at this point. Once the requirements are understood they are recorded in a format all stakeholders can understand after which point the document can be validated for the four properties listed above.

Validating requirements

Lord Kelvin said,

To measure is to know. If you can not measure it, you can not improve it.

This sentiment has been strongly endorsed by modern software companies where common belief says that good decisions are always backed with meaningful metrics. Software systems themselves are no different: when a customer add a requirement to a software system, there is an expectation that that requirement will be delivered. To ensure this, it should be possible to validate that all requirements have been met, and that their implementation is correct.

While for some requirements this can be easy (e.g., “the list should be sortable on both columns”), for others it can be impossible (e.g., “the system shall be performant”). In situations where validation is not easy (or even possible) the requirement is often restated in more concrete terms. For example for performance, concrete targets could be put on disk usage, peak memory usage, throughput rate, peak connected users, or any number of other measurable metrics.

Being able to validate a requirement is clearly advantageous for the customer, but it is also good for the technical team as it makes their “definition of done” extremely clear. In practice measurable objectives are usually achieved, if the objective was unrealistic it should have been caught during requirements elicitation rather than during project acceptance. Being concrete also ensures that stakeholders have consistent expectations about the final product.

References

- A reflection on software being a wicked problem.