Introduction

Software engineering is a broad and relatively young field. Here we will briefly touch on what software is, why it needs to be engineered, and what role the field of software engineering plays in the overall lifecycle of modern software systems.

What is software?

Software is everywhere. It is in our spacecraft, our cars, our fridges, and our phones. While software plays a key role in a diverse set of domains, at its core all software is the same: Software comprises a series of instructions for a computer to execute that consume input, perform computation, and emit output.

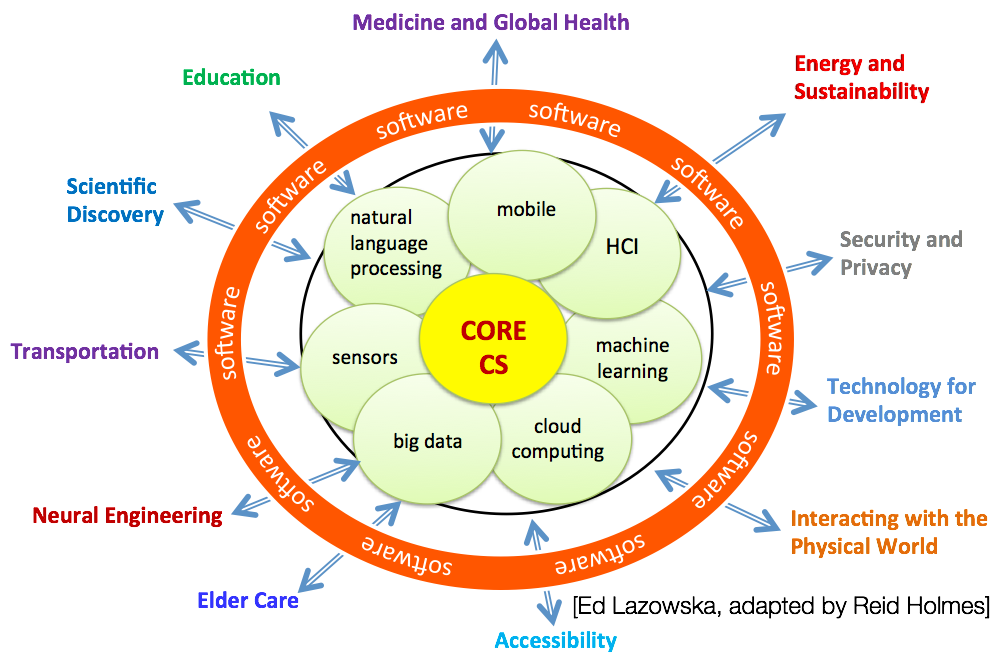

Ed Lazowska provides a great overview of the kinds of impact computer science has on our modern society (I added the software doughnut to his original figure):

Why do we need to engineer software?

Given that a computer will blindly execute any set of syntactically valid instructions it is given, it is extremely important that these instructions be correct. We have all experienced software failures (be them problems that cause a program to crash or require you to reboot your computer) and defects (where the program continues to execute but behaves incorrectly). While these failures and defects are frustrating, the pervasiveness and utility of software means that these problems can have much more serious (e.g., loss of life) or expensive (e.g., hundreds of millions of dollars) implications in some domains.

During his 1972 Turing award lecture Dijkstra said,

As long as there were no machines, programming was no problem at all; when we had a few weak computers, programming became a mild problem, and now we have gigantic computers, programming has become an equally gigantic problem.

Another way to think about this is in terms of trajectory: do you believe that software will play a greater or lesser role in your life 5 years from now? We are increasingly reliant on software systems for a myriad of both life-critical and convenient aspects of our modern lives.

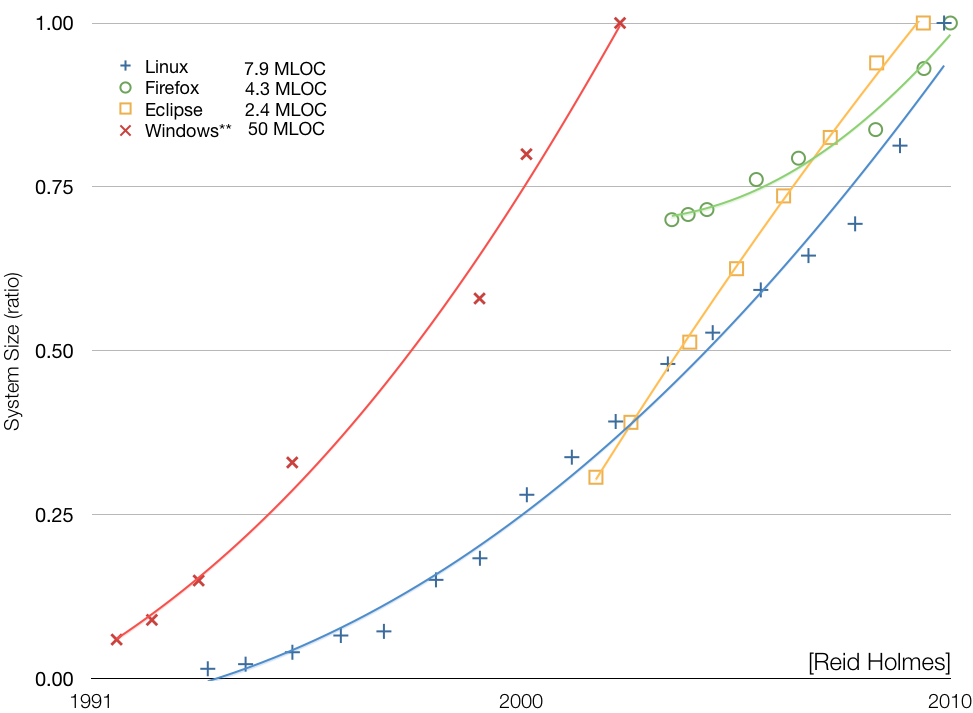

In terms of size, software is rapidly growing. While a decade ago 1 MLOC (Million Lines of Code) systems were somewhat rare, they are commonplace today (with many systems now ranging into hundreds of millions of lines). This explosion in complexity has been driven by our ever-expanding expectations of what software systems should be able to achieve. The growth in size of some common systems is shown below. Managing this level of complexity requires disciplined and intentional engineering techniques.

Along with the size of software systems, their overall cost has also become a major component of industries that were not historically software-heavy. For example, the electronics and software in modern cars represented 40% of the car’s overall cost in 2015 compared to 16% in 1990.1 Similarly, with the complexity issues above, understanding, predicting, and controlling costs of complex systems require incredible engineering effort and skill.

What is software engineering?

Given the description of software above, it might be tempting to define software engineering like:

The process of transforming a mental plan of desired actions for a computer into a representation that can be understood by the computer. [Jean-Michel Hoc and Anh Nguyen-Xuan]

This is a great definition that clearly captures the challenges of mapping from our human-defined goals for a piece of software to a representation of these goals that is executable by a computer. While the mismatch between these two representations might not seem like a big deal, it is at the root of many of the hardest aspects of software development. That said, while computers need to be able to execute software, other engineers need to be able to understand it (as observed by Knuth):

Let us change our traditional attitude to the construction of programs: Instead of imagining that our main task is to instruct a computer what to do, let us concentrate rather on explaining to human beings what we want a computer to do.

Ultimately though, programming is only a small part of what software engineering is all about; a more comprehensive definition is:

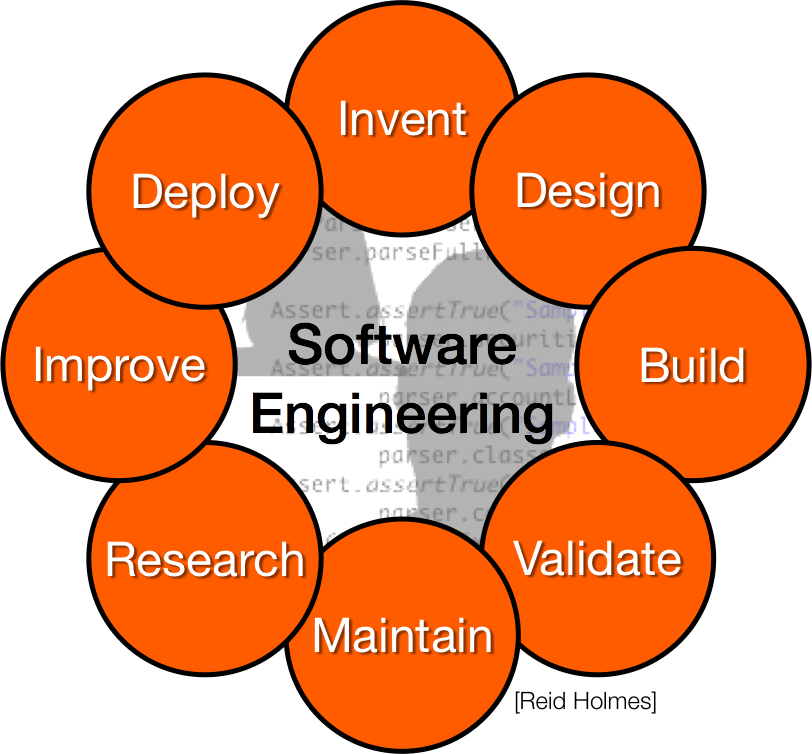

The establishment and application of scientific, economic, social, and practical knowledge in order to specify, invent, design, build, validate, deploy, maintain, research, and improve software that is correct, reliable, and works efficiently on real machines.

This definition captures the range of input skills required to build software (scientific, economic, social, and practical knowledge), the tasks performed by software engineers themselves (specify, invent, design, build, validate, deploy, maintain, research, and improve), and the goals of the process (to build correct, reliable, and efficient systems).

The most obvious difference between the definition of programming and software engineering is that programming itself really only captures the ‘build’ task that is only a small piece of the spectrum of software engineering tasks. While programming software is hard, and is an important and necessary part of the software engineering process, the tasks that come before (like figuring out what to build and how to do it) and after programming (like deploying, maintaining, and evolving an existing system) are often crucial for ensuring that programming effort is effectively applied.

One of the main goals of this course is to give you a deeper understanding and appreciation for the complexity involved in designing, building, and evolving high-quality software systems. To that end, we will be investigating many of the different dimensions of software engineering captured in the definition above.