Automation

Our expectations for modern software systems demand delivering a level of velocity that was not possible in the past. Gone are the days when delivering once every 3-5 years was considered acceptable. Being able to deliver changes on a weekly, daily, or minute-by-minute basis allows software teams to more quickly deliver new products to market or provide more timely bug fixes.

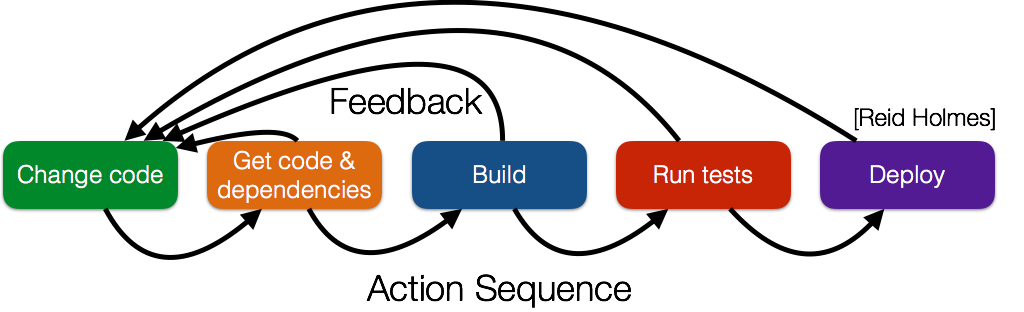

The figure below shows a coarse-grained view of the broad steps required to get a code change deployed in front of a user. While human intervention is required to make every code change, it should be possible to automatically transition from the change in front of a user. The less time this sequence of actions takes (aka the less friction there is in the build process), the quicker the developer can get feedback to refine or roll back their change. Also, the quicker and easier this process is, the more likely developers are to take advantage of it (e.g., if running tests is hard, developers will try not to run them or if deploying is hard developers will avoid deploying fixes that could benefit users unless they are significant ’enough’).

Software systems are increasingly large, distributed, and heterogeneous. Successfully building, testing, and deploying them requires coordinating a huge stack of tools, environments, and systems. This requires a high degree of craftsmanship and has historically involved many manual, laborious, time-consuming, and error-prone steps to translate source code into a shippable executable. The goal of automation is to transform this unsustainable way of building software into a process that is:

- Repeatable: The process of building a product should not vary between different versions of the software (modulo minor improvements over time). A unified building process provides a mechanism for building the system the same way, every time with minimal (preferably no) human intervention required.

- Reliable: If the build process was repeatable but was subject to many non-determinstic failures it would not have value. Being able to trust that the repeatable process will run to its successful completion is crucial, although naturally test failures are sometimes to be expected and are not considered a build automation reliability failure (unless the tests themselves are flaky).

- Revertible: The build process should make it possible to quickly and transparently revert out of any change. If a build is deployed and is found to have an error in production, it should be possible to automatically revert to a prior build in a quick and transparent way.

The gains from automation can be thought of analogously to the gains made when books could be printed with a printing press instead of being written by hand: the setup time is considerable, but the benefits far outweigh these costs in the long run.

Automateable units

Many software building tasks can be automated:

- Source control: Every software team uses version control to track their source code resources (and other assets including any automation tools themselves).

gitandhgare two commonly used version control systems that provide a reliable way to access any past development state. - Dependency management: Code is not developed in isolation; all systems are built upon a host of existing libraries and frameworks. Dependency management solutions provide a means to reliably procure software required for the build process. Common tools include

ant,mvn,npm, andyarn. - Build tools: Compiling the code into shippable units (be they libraries or actual executables) is the next step. While these tasks are sometimes easy, they often involve many independent steps that are joined together by build tools like

make,ant, orgulp. - Analysis tools: Many teams want to have stronger control over their codebase than just ensuring the cod is able to be built. Static analysis tools are commonly used to validate every change to ensure that they do not introduce obvious errors, violate the team’s coding guidelines, or contravene other project policies. For example, linting tools commonly validate changes to ensure that common mistakes that have shown to lead to defects or that decrease the maintainability of the system are not introduced. Many tools employ security checkers to ensure that security policies (like not checking tokens or passwords into version control) are being followed. Finally, tools like checkstyle are widely used to ensure a project’s source code maintains a consistent style which can make it easier for new team members to join, but also makes it easier during code review.

- Test tools: Tests are code too, so enabling them to be written with as little boilerplate code as possible is important for reducing the costs of automated testing. Many unit test tools in particular have been developed to help software engineers write tests and form them into coherent test suites quickly. These tools include

jUnit,NUnit, ormocha. - Test runners: Once test suites have been developed they must be run in a repeatable way. While this can take place on the engineer’s development machine, tests are often run on a common infrastructure to increase the consistency between test runs for all developers. Tools like

Jenkins,Bamboo, andTravisCIall work to execute test suites remotely. These first five steps are often called continuous integration. - Deployment: In the online realm software must be deployed once it is built; this field (often referred to as continuous deployment) is beyond the scope of this reading.

Ultimately effective automation will allow a software system to be checked out, configured with the correct dependencies and tools, built, and unit tested with a single command (or a short sequence of commands that can be placed in a simple script). For example, for the project we can simply run:

yarn install

yarn run configure

yarn run build

yarn run testBy enforcing each step to be executable on the command line without developer intervention, the entire process can happen automatically in the background. For example, after every push to a project’s VCS the whole process can be automatically performed and the results sent to the engineer if any problems are detected.

DevOps

DevOps is a huge space. Here we just mention how automation has enabled many of the advances that enable DevOps to provide value for software teams. DevOps teams take advantage of automation to enable them to quickly deploy (or revert) changes in production. This also enables many different versions of software to be deployed at once. The most common mechanism for this is called the feature flag. Feature flags enable DevOps engineers to turn on and off different features for different users dynamically at runtime.

Feature flags have been extended for several different use cases. The first is for enabling Canary deployments. A new feature can be trialed on small, targeted subsets of users to gather data and ensure that it works in practice before being rolled out to a larger body of users.

Another use of feature flags is for A/B testing. In this form of testing, different versions of the same feature (or a new version of a feature against the baseline version) are are simultaneously deployed so that the impact of the new version can be compared to the other version. While A/B testing is widely used in industry, care must be taken to ensure that users are treated fairly as most system users do not choose to use a system to be subjects in experiments.

An extension to automated tools gaining traction in deployed software platforms is chaos tools. These tools intentionally stress a software system to ensure that its failure and mitigation strategies actually work as intended. This kind of analysis was pioneered by Netflix who are famous for their ‘Chaos Monkey’ that would randomly terminate micro-services in production to ensure that their platform (and clients) would seamlessly recover without any user noticing that this had happened. These advanced tools are valuable due to the complexity of the environments modern systems are deployed within: while a failure strategy might look good on paper, only through runtime experimentation can a team actually validate that it works properly in practice. Without advanced automation though, teams would be unwilling to perform this kind of dramatic action in production without knowing they can quickly and easily bring the system back up to its regular operation.

Package Versioning

As a part of automated build processes, new software versions are constantly being created. Communicating the meaning of these changes in valuable to all consumers of a software package. Additionally, how packages your software depends upon have changed can also have important ramifications for your upgrade decisions.

Semantic Versioning, often referred to as SemVer, is a versioning scheme that is commonly used to convey meaning about the underlying changes in a release. Semantic version numbers consist of three parts: MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH. Each part is an integer that can only be incremented. Leading 0s are not permitted, unless the part is actually 0 (e.g. 1.02.2 is invalid, but 1.0.2 is fine).

MAJOR: Incrementing the major version indicates that there are incompatible changes in the API which may affect any client of the package. For example, it is not uncommon for a major version change to cause existing clients of a package to fail to compile.

MINOR: Incrementing the minor version indicates that new features have been added, but these should not affect the compilation (or operation) of existing clients. Minor versions often introduce new APIs.

PATCH: Incrementing patch versions should never affect any clients and are typically used to distribute bug fixes.

When the MAJOR version is 0, a package is considered pre-release and any version change should be treated as a breaking change. It is common to add a suffix after the PATCH version, separated by a +, for example 2.12.7+20251123. These suffixes are often used to capture new builds that do not necessarily even contain changes that reach the threshold of a PATCH (e.g., documentation or logging changes).

Upgrading and Downgrading Versions

Upgrading: You can safely upgrade the MINOR and PATCH versions as they are backwards-compatible. Upgrading the MAJOR version requires careful consideration as it may introduce breaking changes. In terms of risk, upgrading PATCH versions should always be safe and upgrading MAJOR versions is frequently not safe.

Downgrading: Downgrading the PATCH version is generally safe as it only involves bug fixes. Downgrading MINOR versions can be safe, as long as you have not taken a dependency on an API that was added to the MINOR version you depend on.

Downgrading to a library with a preceding MAJOR version is likely to cause problems. In general, downgrading MAJOR and MINOR versions carries risk and is generally avoided.

Upgrade policies are often captured in metadata files for a project. For example, the following three lines describe alternative upgrade paths:

"parse5": "^7.1.1",

"typescript": "~5.3.2",

"mocha": "10.0.2"In this example, the ^ for parse5 specifies that upgrades to MINOR and PATCH versions are permitted. The ~ for typescript specifies that upgrades to only the PATCH field is permitted. The declaration for mocha specifies that only that single version is acceptable.

References

A humorous discussion of automation can be found in the Phoenix Project.

Nice set of build automation slides.