Asynchronous Programming

Over the past decade, advances in computers have happened through increasing the number of cores within a processor rather than raw clock speed. To take advantage of this, most modern programming languages support some model concurrent execution. While at its core the code you write in JavaScript (and by extension TypeScript) can only execute in one thread, a thread pool does exist in both Node and the browser to ensure that long-running tasks can be offloaded in a way that does not block the main thread. The model supported by JavaScript is that of asynchronous execution.

In JavaScript functions execute on the call stack, and they always execute to completion. Since only one method can execute at a time and another cannot run until the first finishes, it is important that JavaScript functions do not take ’too long’ to execute. While ’too long’ can be difficult to define, in JavaScript the most commonly held measure is 16 ms; exceeding this value will cause the UI to miss a refresh on a 60 Hz monitor. Stuttering caused by computations exceeding these thresholds are referred to as ‘jank’ within the browser. Rick Byers has a nice Jank demo where you can see the impact of work on the main thread with respect to UI updates.

In practice, many operations take more than 16 ms to happen: network latency can range into hundreds of milliseconds, and reading or writing from disk can easily take more than a second for larger files. Since these are relatively common operations, JavaScript has a thread pool that has limited capabilities but is ideal for handling blocking operations (e.g., network and file IO, long-running tasks, timeouts, etc.). Rather than executing on the main thread, these execute in a separate thread pool and are returned to the call stack via callbacks when the event loop is idle.

Philip Roberts has created a great video for understanding the event loop. He also developed a cool tool for visualizing how the event loop works.

The Async Cookbook contains many code-forward examples demonstrating how to call and test asynchronous methods using callbacks, promises, and async/await.

Callbacks

Shortcomings

Two common problems manifest with callbacks in practice. First, handling errors is challenging because callbacks are invoked, but they do not return a value. This means any information about the execution of the function making the callback must take place in the parameters. Node-based JavaScript addresses this with the error-first idiom. For example:

fs.readFile("/cpsc310.csv", function (err, data) {

if (err) {

// handle

return;

}

console.log(data);

});It is only by convention that err is passed first; this depends on the developer doing the right thing and on clients checking err to see if it contains a value and acting appropriately if it has.

This problem becomes harder to manage once callbacks depend on the output of previous callback functions; this is extremely common (e.g., read a directory list (async) and then read a specific file (async)). This pattern arises from our natural desire to want the apparent execution to proceed from top-to-bottom in the source code file. This style of error handling is much like you would see in C code where return values were checked for error statuses (instead of the error being in a function param). One significant problem with callback-based error handling is that exceptions cannot be effectively caught. That is, since the callback is not being executed in the context of its originating function, there is no ‘parent’ method for the catch to exist in. More details and tips about this can be found here. Nested callbacks are often referred to as callback hell.

fs.readdir(source, function (err, files) {

if (err) {

// handle

} else {

files.forEach(function (name, index) {

fs.stat(files[index], function (err, data) {

if (err) {

// handle

} else {

if (data.isFile()) {

fs.readFile(files[index], function (err, data) {

if (err) {

// handle

} else {

// process data

}

});

}

}

});

});

}

});Promises

Promises are a mechanism to address two of the largest shortcomings of callback hell, namely:

- Flattening callback chains; and

- Enabling try/catch for error handling.

Although promises do enable try/catch to work properly, they do not provide any functionality that would not be possible with callbacks alone. Their main benefit is that they are easier for developers to read and understand, making it more likely that developers will ‘do the right thing’ in these often-complex program sequences. Adapting the callback example from above, a promise-ified version would look like:

var file = null;

fs.readdir(source)

.then(function (files) {

file = files[0];

return fs.stat(file);

})

.then(function (fileStat) {

if (fileStat.isFile()) return fs.readFile(file);

})

.then(function (fileData) {

// process data

})

.catch(function (err) {

// handle errors

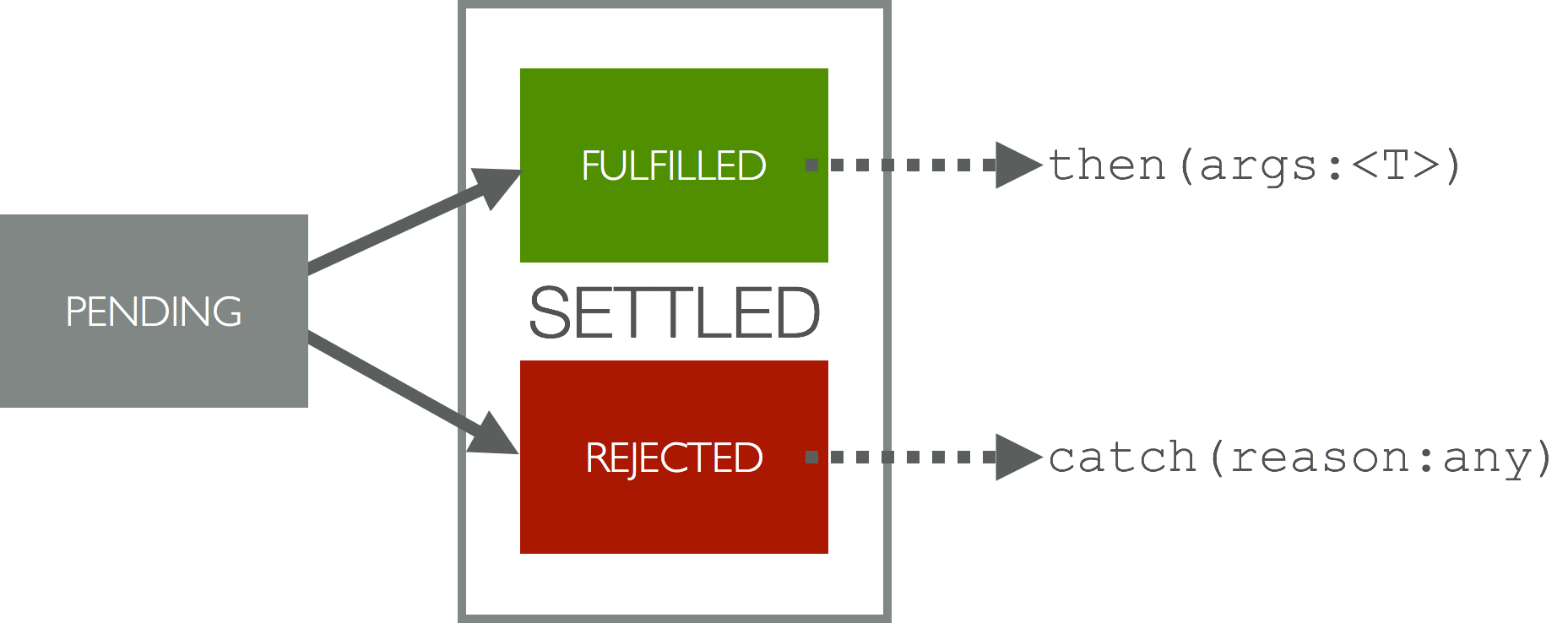

});Promises can only have three states, pending before it is done its task, fulfilled if the task has completed successfully, and rejected if the task has completed erroneously. Promises can only transition to fulfilled or rejected once and cannot change between fulfilled and rejected; this process is called settling. HTML5Rocks has an extremely thorough walkthrough of promises where you can see how many of its features are used in practice.

At their core, promises are objects with two methods then and catch.

then is called when the promise is settled successfully while catch is called when the promise is settled with an error.

These methods both themselves return promises enabling them to be chained as in the example above (three then functions called in sequence).

It is important to note that there can also be multiple catch statements (e.g., in a 5-step flow you could catch after the first two, fix the problem, and then continue the flow while still having a final catch at the end).

One nice feature of Promises is that they can be composed; this is especially helpful when you are trying to manage multiple concurrent promise executions in parallel. This is the explicit goal of Promise.all:

let processList: GroupRepoDescription[] = [];

for (const toProcess of completeGroups) {

processList.push(gpc.getStats("CS310-2016Fall", toProcess.name)); // getStats is async

}

Promise.all(processList)

.then(function (provisionedRepos: GroupRepoResult[]) {

Log.info("Creation complete: " + provisionedRepos.length);

// can also iterate through the individual results

})

.catch(function (err) {

Log.error("Creation failed: " + err);

});Analogous to Promise.all is Promise.race.

This allows for starting multiple async calls; then is called when the first promise fulfills, rather than when all of them fulfill as is required for Promise.all.

Promise.race can be handy when there are multiple ways to achieve a task, but you cannot know which will be fastest in advance, or if you want to show progress on a task by updating the user when data starts to become available rather than waiting for a full operation to be complete.

When working with promises, it is strongly encouraged that you end every then sequence with a catch even if you do not do any meaningful error handling (like we do above).

This is because promises settle asynchronously and will fail silently if rejections are not caught; they will not escape to a global error handler.

Another common mistake when working with promises is that then is not applied to the right object.

In the above example if you called then inside the for loop you would not be notified when all promises are done but one-by-one as they execute.

Adding verbose debug messages can really help here, so you can keep track of the order your functions and callbacks are executing.

References

Discussion of some challenges with concurrent programming.

Mozilla event loop overview.

Article about the event loop with more examples.

Article about the event loop that includes some detail about closures.

A collection of promise use cases can be found here and further examples.

While promises seem really fancy, how they are implemented is relatively straightforward (or even more straightforward).

Sencha also has a nice promise intro.

Callback, Promise, async/await concrete example.

Async/await will eventually supplement promises, although they are still really new language features.